What do these photos have in common?

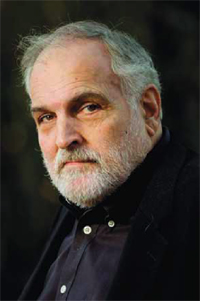

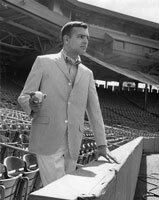

The photo on the left shows John Billheimer in Fenway Park when he was a graduate student at MIT and took on odd modeling jobs for Filene’s Department Store. The photo on the right shows John Billheimer today.

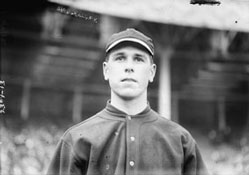

The photo on the left shows Fred Snodgrass, 1912 centerfielder for the New York Giants. In the final game of the 1912 World Series, Snodgrass dropped an easy fly ball off the bat of the first Boston Red Sox hitter up in the bottom of the tenth inning. Boston eventually scored two runs to erase a one-run Giant lead and win the World Championship. Snodgrass’s error became known as the “$30,000 muff,” the difference between the winner’s and loser’s share of series gate receipts. After a nine-year career with the Giants, Snodgrass went on to become a successful banker and rancher and the mayor of Oxnard, California. Yet when he died in 1974, the New York Times headline for his obituary read: FRED SNODGRASS, 86, DEAD. BALL PLAYER MUFFED 1912 FLY.

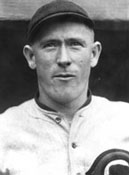

The photo on the right shows Max Flack, 1918 centerfielder for the Chicago Cubs. In the final game of the 1918 World Series, Flack dropped a fly ball that allowed the only two Red Sox runs of the game to score and sent his Cubs down to a 2 to 1 defeat. Although Flack’s muff was arguably more costly than that of Snodgrass, since it allowed two runs to score, while Snodgrass’s merely allowed the tying run to reach base, the New York Times didn’t bother to note Flack’s passing with an obituary, let alone chide him for missing an easy fly.

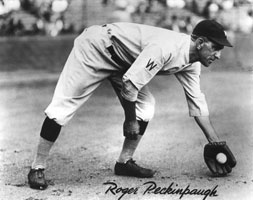

The photo on the left shows Roger Peckinpaugh, shortstop of the Washington Senators and American League Most Valuable Player (MVP) in 1925. In the 1925 World Series, Peckinpaugh put on one of the worst fielding exhibitions ever recorded, making eight errors in seven games and costing his team at least two games and the world championship. His eight errors still stand as a Series record, and prompted the major leagues to put off MVP voting until after the World Series was over. His fielding record in the 1925 Series haunted Peckinpaugh for the rest of his life. In his later years, he was quoted as saying “Why do you want to know about that goddamn record? I played in three World Series. I was the most valuable player and I was a major leaguer for eighteen years… And all you want to know about is that goddamn record for errors.”

The photo on the right shows Hall of Fame shortstop Honus Wagner, who held the record for World Series errors for 22 years before Peckinpaugh broke it in 1925. In the first World Series, held in 1903, Wagner made six errors for the losing Pittsburgh Pirates and struck out to make the final out of the Series. One of the premier players of his day, and arguably one of the five or six greatest players of all time, no one suggested that Wagner be fitted with permanent goat horns for his performance in the 1903 Series.

Photos of Snodgrass and Wagner courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Photos of Flack and Peckinpaugh courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, NY.

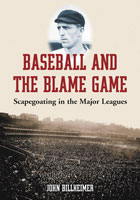

On the left is another early photo of John Billheimer on a modeling assignment in Fenway Park. He is standing in front of the left field wall, and his son, on seeing the picture said, “Tell me again, which one is the Green Monster?” On the right is the cover of Billheimer’s new book BASEBALL AND THE BLAME GAME (McFarland Press, Summer 2007). In it the author asks why some players, such as Bill Buckner, Fred Merkle, Roger Peckinpaugh, and Fred Snodgrass, have been damned for life for miscues made on the baseball diamond, while other players have made the same mistakes under the same circumstances without wearing goat horns to their graves.